Please follow us on Gab, Minds, Telegram, Rumble, GabTV, Truth Social, Gettr

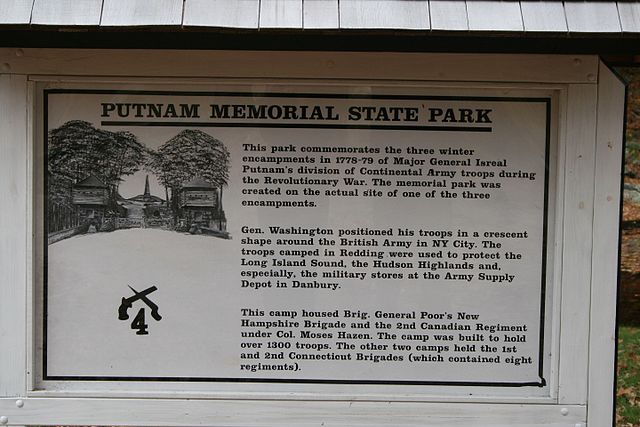

During this time of trial for the United States, it is worth remembering those who came, and fought for freedom, before us. If you live in New England, Connecticut's Valley Forge, or Putnam State Park in Redding, is a must see for your entire family.

The site is a former encampment of the Continental Army during the 1778-1779 winter. The piles of stone lined up down the long thoroughfare mark where the chimneys stood for the wooden structures.

I can assure you, the images will be forever with my young sons as their eyes opened wide at the stories told by the park guides of these brave men so long ago, who gave their all for our nation and our way of life.

The following information was taken from: “The Winter Campaign of Starving” Archaeological Investigations at Putnam Memorial State Park in Redding and Bethel Connecticut. By Ricardo J. Elia and Brendan J. McDermott

Creation of the Israel Putnam Memorial Camp Ground

When the army broke camp, in accordance with custom, the barracks were burned, the chimneys fell in different directions which is still distinguishable in most cases, and then with time became apparently only heaps of stone. (Report 1903: 8) *Recent research indicates the barracks were not burned, wood was valuable back then.

The deserted camp ground was left to its former solitude, and in the course of a few years, became overgrown with trees and a thicket of underbrush; and it was not strange, that after the passing of a few generations, even the location, or the history of the camp ground, was almost unknown. (Report 1915: 8)

The movement to preserve and memorialize the site of the winter quarters of 1778-1779 in Redding began in the late 19th century. Although the details of this movement are not recorded, it is likely that the initial efforts were made by local citizens of Redding, especially Charles B. Todd, the local historian, and Aaron Treadwell, the landowner who donated the first tract of land that would become the Israel Putnam Memorial Camp Ground.

The first official action leading to the creation of a state park on the site of the encampment at Redding was the passage by the Connecticut legislature, in January, 1887, of a resolution to establish a committee “to investigate and report at once on the practicability and desirability of obtaining for the State the old Israel Putnam Camp Grounds in the town of Redding, on which traces of said encampment still exist, and the erecting thereon of a suitable monument or memorial” (Todd 1913: 7). The legislative committee visited the site in February, 1887, which they described in a special report, dated February 9.

The heaps of stone marking the site of the log huts in which the brigades were quartered, are forty-five in number and are arranged opposite each other in long parallel rows defining an avenue some ten yards wide and five hundred feet in length. These, with others scattered among the crags, admirably define the limits of the encampment, and form one of the best preserved and most interesting relics of the Revolution to be found in the State, if not in the Country. It was here that Putnam and his brigades wintered in ln 1778-9. (Bartram 1887: 40-41)

The committee also reported that Aaron Treadwell, the owner of the site, was willing to donate the land to the state. The committee recommended that the state accept this offer and appropriate $1500 for the purpose of erecting a memorial on the site. The Connecticut legislature passed a resolution accepting these recommendations on May 4, 1887 (Todd 1913: 9).

Accordingly, on August 17th, 1887, Aaron Treadwell gave a 12.4 acre parcel to the state for the sum of “$1 and other considerations (Redding Land Records 25: 80-82, hereafter RLR).” This property, the first building block in the eventual construction of the park, may have been the same one purchased by Treadwell on June 28, 1877 for $110 from Henry H. Adams viz:

…a certain piece of land situated in said town of Redding at the “Old Camp” so called containing 12 acres more or less and bounded north by land of (Harsock?) Read East by heirs of Isaac H. Bartram South by Highway and West by Sherman Turnpike so called in part and in part by land of grantee… (RLR 24: 63).

This, in turn, may have been purchased by Adams on April 6, 1865 for $150 from Sally and Huldah Read:

…a certain piece of or parcel of land lying in said Redding at the Old Camp so called in quantity 12 acres bounded south by highway, east by heirs of lsaac Bartram North by Hannah Read West by Sherman Turnpike in part & in part by Aaron Treadwell (RLR 21: 154).

At this point it is impossible to follow the deed trail back any further. There is no indication of from whom Sally and Huldah Read purchased the property. There is only one other reference to the “Old Camp” when Aaron Treadwell purchased an adjacent parcel on April 9, 1879 for $450 from Joseph Hill:

…quantity 18 acres more or less at Old Camp so called the same being pasture and woodland bounded North by heirs of Benjamin B. Read east by an old road formerly Sherman Turnpike south by highway leading from Lonetown Schoolhouse… (RLR 24: 298).

From the beginning, the purpose of preserving the site of the encampment was to commemorate the winter quarters, not to create an area for recreation. In a plan presented to the legislative committee that visited the site, Charles B. Todd explained the rationale behind the park.

It is not proposed to erect a pleasure park, but a memorial. The men it is designed to commemorate were strong, rugged, simple. Its leading features, therefore, should be of similar character and of such an historical and antiquarian cast as to direct the thought to the men and times it commemorates. The rugged natural features in which the proposed site abounds should be retained. (Todd 1913: 7).

Todd proposed adding some new features to the site, while preserving intact the main line marking the remains of the encampment:

I would throw over the brooks arched stone bridges with stone parapets such as the troops marched over in their campaigns through the Hudson valley. The heaps of stone marking the limits of the encampment should be left undisturbed as one of the most interesting features of the place. One might be reconstructed and shown as it was while in use. A summer house on the crag guarding the entrance, might be reared in the form of an ancient block-house, like those in storming or defending, which Putnam and his rangers learned the art of war. Such a structure, at this day, would be an historical curiosity… (Todd 1913: 7-8).

It was also recommended to erect a monument on the parcel to commemorate Putnam and his troops. In 1887, a sketch was made of the encampment site on the portion of the Treadwell property that would be donated to the state in the following year. This plan, entitled “Plan of Camp ground of Gen. Israel Putnams’ [sic] Soldiers During Winter of 1778-1779 in Redding, Connecticut,” is located in the Redding Land Records (vol. 25, p. 81), and is shown in Figure 11. As the earliest sketch map of the site, this plan is of considerable interest. In addition to showing the boundaries of the 12.40 acre Treadwell property, the plan identifies several features that were believed to be related to the 1778 & 79 encampment. These include an “old road built by Putnams [sic] soldiers;” a single hut and the “camp guard quarters,” located in a “grove;” the main “line of soldiers huts,” consisting of a double row of “remains of chimneys;” and a cluster of “officers’ quarters” located near the monument.

Park “Improvements”

The granite obelisk monument was built in the summer of 1888 under the supervision of a committee appointed by the governor. This committee, during its work, had noticed that “the tract of twelve acres which had been presented by Mr. Treadwell very inadequately preserved the autonomy of the former camp. The line of barracks originally extended through the adjoining fields north nearly a quarter of a mile….” (Todd 1913: 9). This discovery led to the acquisition of additional land so that the entire winter camp might be included in the park. The Read property on the north of the Treadwell parcel (Plan 1) was purchased by O. B. Jennings and donated to the state on February 10, 1888 for “$1 and other good considerations (RLR 25: 90).” This parcel of almost 30 acres included the hill later crossed by Overlook Avenue, the so-called bake oven, and an additional area of firebacks; later Jennings gave another 52 acres of wooded land west of the camp grounds (RLR 27: 5). Twenty acres at the northern end of the camp, including the area around Philip’s Cave, the “officers quarters, and the armies entrance into the camp, were purchased and donated by I. N. Bartram (Report 1903: 10).

Two last donations completed the historical nucleus of the park. A gift of “7 acres 46 sq rods” was made on July 26, 1893 by Helen and Isaac Bartram (RLR 25: 301-3). This completed the circuit of Overlook Road. The property comprising the entrance to the park on either side of the Sherman Turnpike was given on July 23, 1889 by Aaron Treadwell (RLR 25: 150-52). All of these donated parcels can be picked out individually on the 1890 surveyed plan of the park, although how the Bartram donation of 1893 can be recorded on an 1890 plan is unexplained.

The activities relating to the creation and maintenance of the Israel Putnam Memorial Camp Ground were managed by a board of commissioners appointed by the Connecticut General Assembly (Fig. 12). The commissioners reported on their activities beginning in 1889 and every two years thereafter between 1903 and 1915; these reports were published by the slate and are preserved. The report covering the 15-month period ending September 30, 1902 is particularly useful, because it contains a comprehensive summary of legislative actions, reports, expenditures, and lists of commissioners from the early years of the movement to create a state park (Report 1903).

Other data relating to the management of the park include the record of minutes of meetings of the Putnam Memorial Camp Commission. These records are incompletely presented at the existing museum in the park. They include an original leatherbound book containing meeting minutes from July 11, 1901 to August 26, 1909; copies of minutes for the period July 14, 1911 through June 6, 1917; a folder containing original and carbon copies of minutes of the commissioners’ meetings from July 7, 1921 through October 18, 1923; and carbon copies of minutes from 1947-49.

In addition to the records pertaining to the commissioners’ meetings and park activities, a series of maps and plans relating to the park was examined during the course of the survey. These documents were found in two places: the existing museum, on the park grounds, and in the files of the state Department of Environmental Protection in Hartford.

The erection of the monument occupied the attention of the park commissioners during 1888 (Bartram et al. 1889: 43-44). Immediately thereafter, work began on the construction of the park entrances, roads, bridges, and other features. Most of the area was wooded and overgrown when the park was created. According to the 1887 legislative committee’s report, “a fine forest covers the greater portion of the site” (Bartram 1887: 40-41). The commissioners’ report for 1889-90 describes the early work in the park:

Active work was begun at once in clearing under-brush and rock from the grounds, building drives, walks, log-barracks, and block-houses. We found the grounds rough and stubborn to clear. Much of the timber had been cut, leaving large and obstinate stumps to remove. We were forced to make many changes from the plans, as were they followed out, it would mar the beauty of many of the fine features of the camp, and come in contact with the fire-backs. These changes were made only after a careful consideration and by a vote of the Commission. (Report 1893: 51).

These features–the antiquarian infrastructure of the park–were described in the parlance of the time as “improvements.” The 1889 committee’s report detailed some of the specific plans that were underway in the park (Bartram et al. 1889: 46-47): estimates were prepared for the construction of a main avenue (later called Putnam Avenue), side avenues, ways, and paths; for the construction of block houses and gates at the park’s entrance; for the construction of a masonry dam; for bridges, culverts, stone and iron fencing, and gates; and for the building of “6 barracks with chimneys or log huts in ye olden time of 1778, at $200 each.”

One of the most important activities during the early years of the park was the clearing and landscaping of the terrain around the stone piles that marked the remains of the soldiers’ huts during the encampment of 1778-79. While the park records make it clear that the preservation of the firebacks and other remains of the 1778-79 encampment was of paramount importance, it is also clear from a review of the records, supplemented by the evidence of archaeological testing, that the remains of the original camp suffered a great deal of disturbance from the methods that were employed by the early park to “restore” them. These included grading, landscaping, and removing trees, stumps, and stones, and it seems probable that most of the firebacks (in the main double row along Putnam Avenue, at least) were systematically cleaned out, their artifacts removed; some were certainly rebuilt, including several in the vicinity of the monument. The remains also suffered from the fact that in several areas (the guard house, log barrack, and stone barrack) modern reconstructions were built directly on top of the original ruins.

It is sufficient to point out here that Revolutionary War period artifacts were regularly discovered and collected from the site during these activities. We also learn from the inventory of “relics” deposited in the park’s museum that many were collected by Thomas Delaney, who served for 24 years as the park’s first superintendent; in that capacity he was in charge of much of the grading around the firebacks Among the artifacts in the museum were:

Box of Bullets and Grape Shot found on the grounds, donated by Thomas Delaney.

Wood with Bullets imbedded in it, found on the grounds, donated by Thomas Delaney.

Old Gun Barrel, found on grounds, donated by Thomas Delaney. (Todd 1913: 45)

The network of roads and paths created in the first few years of the park still exist today and serve to define the limits of the main encampment. These roads, which were all named, are shown on the 1890 plan; the park records (Report 1903: 11) list the principal roads and their names:

Putnam Avenue, the main avenue through the middle of the grounds.

Overlook Avenue. runs over Overlook Hill on the west side of the park.

Sustinet Avenue, passes up the west side of Prospect Hill.

Terrace Road, runs parallel with Sherman Avenue separated from it by the retaining wall.

Sheldon Avenue. connects the entrance. Putnam Avenue and Overlook Avenue on the south.

Huntington Avenue, connects Sustinet Avenue, Putnam Avenue and Overlook Avenue on the north.

The origin of the toponymy seems to be a mixture of historical associations and topographical descriptions. Putnam, Huntington, and Sheldon avenues were named for generals who were associated with the encampment: Major General Israel Putnam, who commanded the three brigades that wintered in Redding in 1778-79; Jedediah Huntington, commander of the 2nd Connecticut Brigade; and Elisha Sheldon, who commanded the state cavalry corps. (Sheldon and his troops were mistakenly believed to have spent the winter in Redding; in fact, they were stationed at Durham, Connecticut). The origin of the name of Sustinet Avenue is obscure, although it may have derived from the Connecticut state motto, Qui transtulit sustinet (“He who has transplanted will sustain”). Overlook and Terrace avenues were obviously named for topographical features.

Also built by the turn of the century were the main entrance to the encampment, with its substantial stone bridge, blockhouses, and gate posts; a “rustic bridge” and smaller blockhouses at the north entrance to the camp, on the Sherman Turnpike (Route 58); a pavilion (1893); horse sheds; a “work shop,” moved to the park in 1896; and a “rustic arbor” (Report 1903: 11).