If you've been to New York City, you've likely noticed the scaffolding. It's everywhere. A blight on the often stunning architecture of America's most storied city. Take a walk and count the sheds (that's what they call the plywood and steel scaffold tunnels built over the sidewalks). Depending on the neighborhood, there's roughly one per block. Sometimes entire blocks--all four sides--are shrouded in scaffolding, pedestrians darting through the makeshift tunnels like so many ants.

New York has more scaffolding than any major Western city in the world, more than 400 miles of it. Sometimes scaffolding goes up and no work is done for years. In one case in Harlem, a building was wrapped for 21 years. 409 Edgecombe Ave. in Sugar Hill was liberated in December of 2023 after over two decades of the same scaffolding. Residents have no recourse, and landlords are often confused by details of the arcane law. NYC is such an outlier in this regard, nationally and globally, that residents have begun to ask questions. Why so much red tape? Who profits?

Call it the legacy of Grace Gold. A Barnard student, Gold was running errands on the evening of May 16th, 1979 when she was struck by falling debris. A 10 lb. chunk of terra cotta had broken off of a lintel on the 8th floor of a building on W. 115th Street. Gold was killed instantly.

As sometime happens when an accident claims a young or gifted victim--and Gold was both--the public connects with the story. Soon, politicians and lawyers smell an opportunity, and in short order, there's a new law on the books. Such was the case with Local Law 10, also known as the Facade Inspection Safety Program (FISP). It stipulated that all buildings six floors and higher must be inspected every five years. Reports were filed with the NYC Dept. of Buildings. Significantly, visual inspections sufficed: a telephoto lens or binoculars were commonly employed by city inspectors.

In the two decades after Local Law 10 was passed, a handful of accidents similar to Gold's took place. As a result, Local Law 11 is much more strict, requiring the erection of sheds and scaffolding, among other stipulations. Building owners incur steep fines and face possible criminal charges for failing to comply with the law.

The idea behind the law is, of course, safety. "Do it for Grace Gold," they said. "Stop bricks from falling on us," they said. But at some point, the question must be asked: what happens when there's too much safety?

The answer is rats, and litter, both of which the sheds attract. Don't forget criminals seeking dark corners, and the homeless/mentally unwell, seeking cover. Even worse, every so often an article pops up concerning New Yorkers injured by falling/collapsing scaffolding. In one such case in 2021, a construction worker was killed, and three others injured. Both ironic and sad.

The only upside to a sidewalk shed? When it's raining and you have to take the dog out. Just mind the raccoons.

In a Daily News article from November of 2023, a reader named Paul Yannolo expressed the frustration and suspicion of millions of New Yorkers quite clearly:

Are building façade rules really about safety?

Manhattan: I am writing this letter about Local Law 11 that New York City buildings are required to comply with. I think it is riddled with corruption. Why is it necessary to have buildings examined every five years to determine if their bricks and mortar are stable? I believe it’s because the unions and other organizations involved in this city’s construction industry, backed by organized crime, receive a large amount of the money spent during these undertakings.

The law was passed during the Ed Koch administration, one of the most corrupt in the city’s history, with the Mafia infiltrating most businesses. Thus, every five years, many residential and commercial buildings must fork over hundreds of thousands of dollars to ensure that the buildings’ façades are safe. It’s the main reason there’s scaffolding all over the city, blighting the sightlines for all New Yorkers.

It’s important to note that buildings have stood in this city for decades without a single instance of falling bricks. Perhaps examining them every seven or 10 years for such problems would be fair, but not every five years. And who’s to prove that there is damage to a building within a five-year period if no one is verifying what the engineers and workers are doing? Buildings that are hundreds of years old in Europe and other parts of the world have remained without incidences of falling bricks or other issues.

This law needs to be either repealed or amended so that it isn’t so blatantly abusive and costly. Most New Yorkers (especially transplants) don’t know the history behind it and either don’t care or don’t understand it. Paul Yannolo

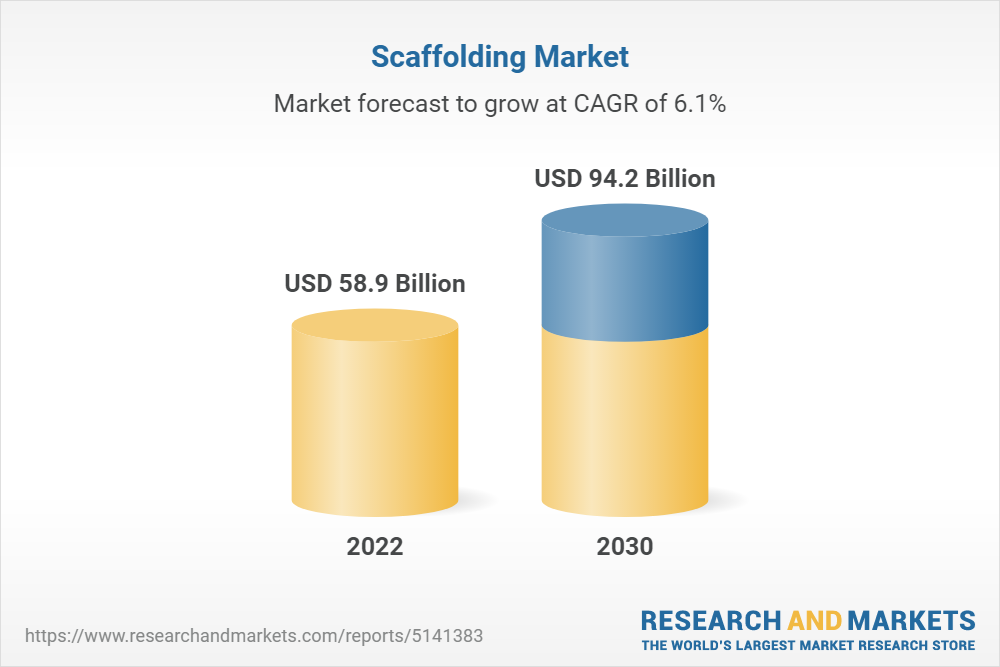

In a $60 billion annual industry that affects millions of people on a daily basis, oversight is needed. Oversight with teeth. The problem of sidewalk sheds began with Mayor Koch, and has only grown worse from David Dinkins to the current resident of Gracie Mansion. Adams has paid lip service to the idea of cleaning up both the Covid-era outside dining sheds and the FISP scaffolding and sidewalk sheds. Is he serious or not? There are far fewer outdoor dining areas now since Adams took office, but there is also far less demand.

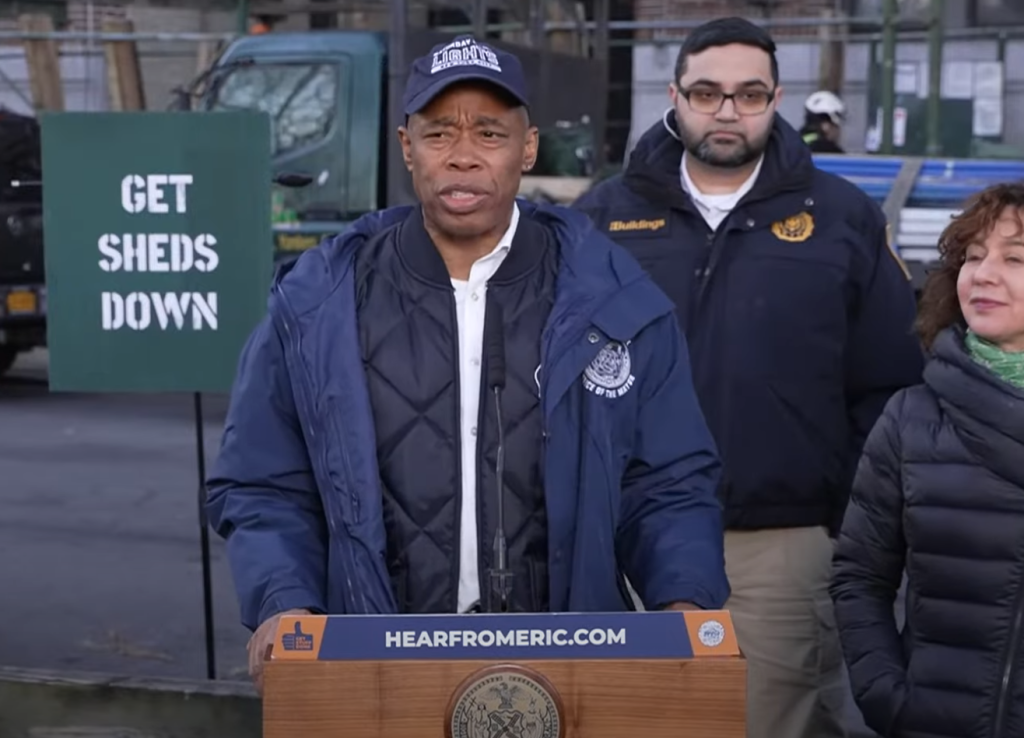

As Adams claimed in a July 2023 speech outlining his vision, “This plan will flip the script so that property owners are incentivized to complete safety work and remove sheds instead of leaving up these eyesores year after year."

As in all matters political, time will tell. The battle will be fought between Adams' desire for a public win, and the billions flowing into the pockets of local contractors. According to an October 2021 article in the New York Times, "Many of [Adams'] donations came from landlords and developers, including William Blodgett, the co-founder of Fairstead; the Durst Organization executive Alexander Durst; Anthony Malkin, chairman of the company that owns the Empire State Building; and Joseph Sitt, chairman of Thor Equities Group."

Presumably, this bodes well for the anti-shed crowd. City landowners don't like having their properties covered in scaffolding every five years for repair. TheManhattan will update this story as needed.